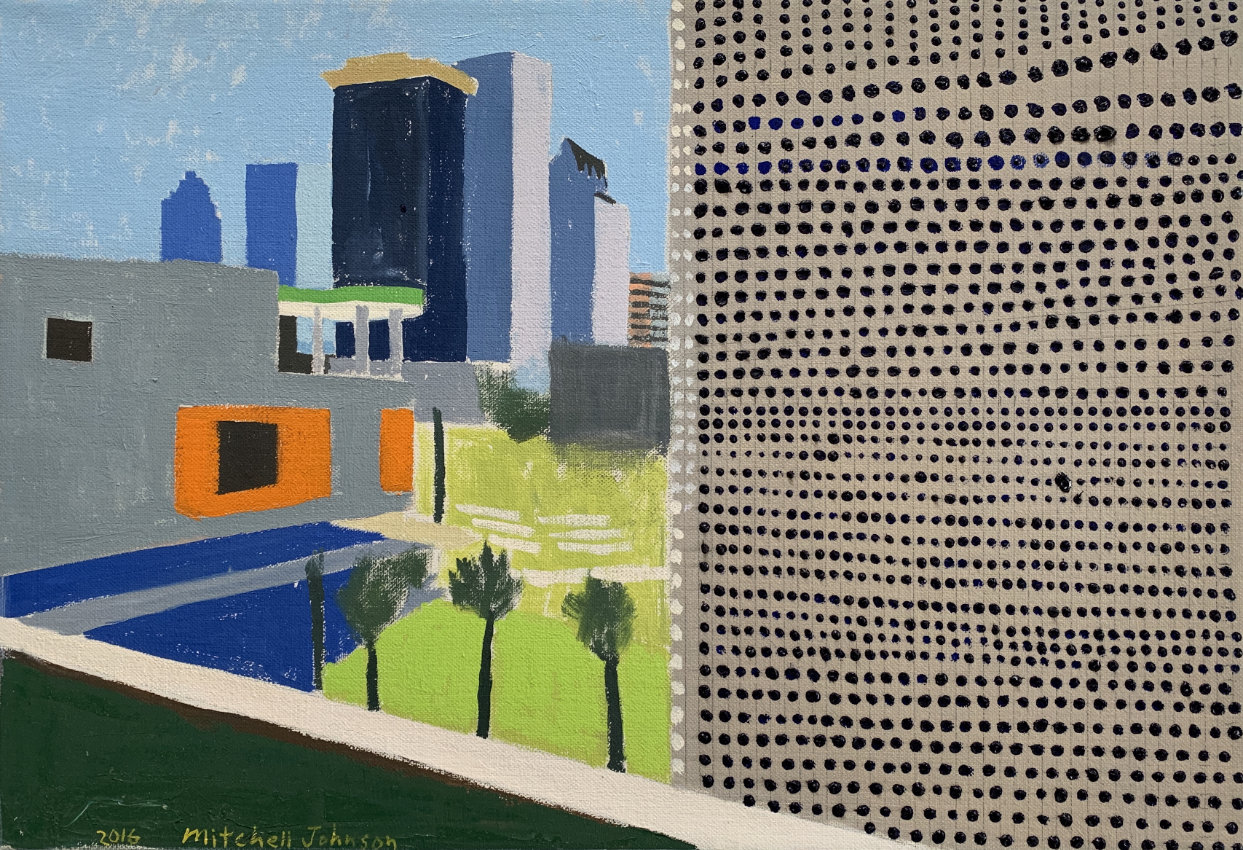

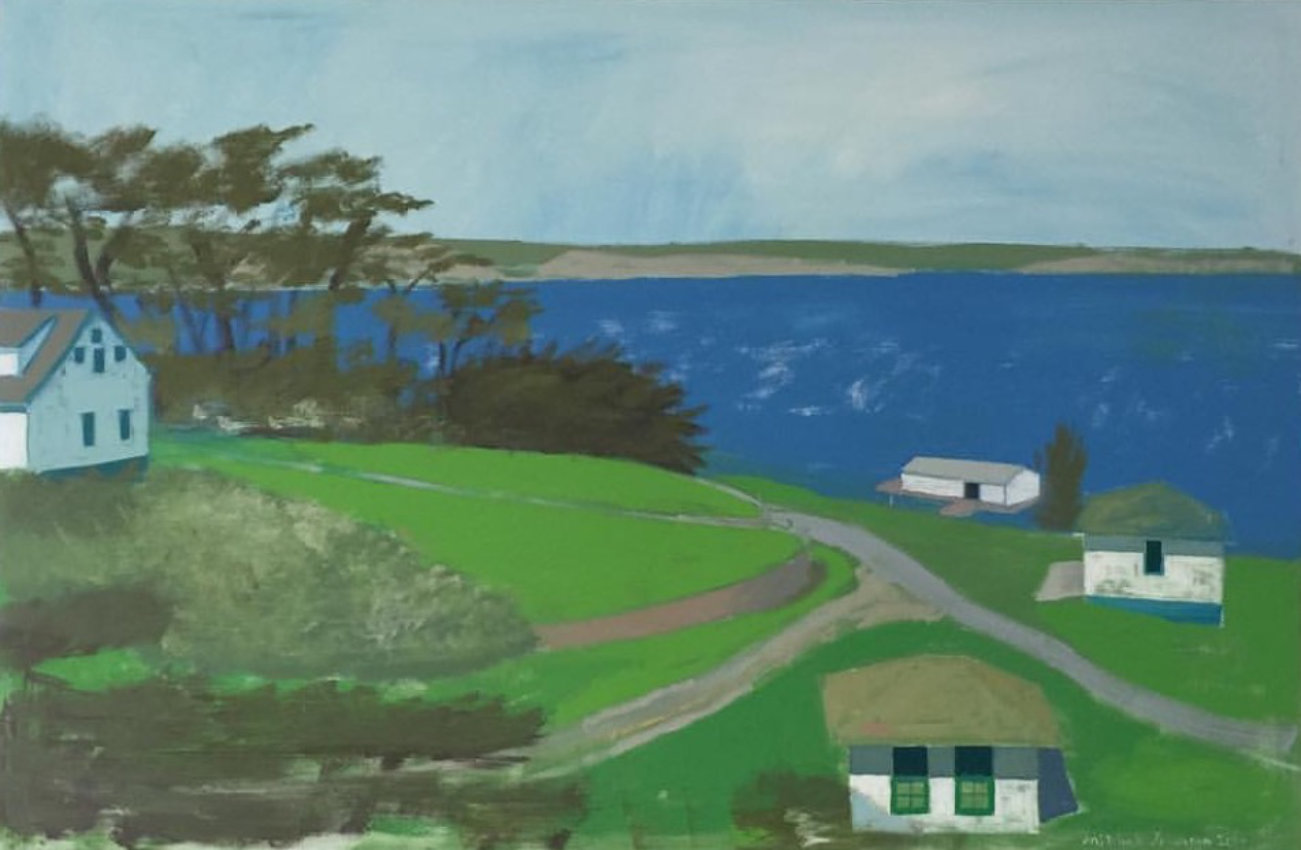

I’m pleased to share my email interview with Mitchell Johnson, well known for his brilliant, painterly landscapes and abstractions, who writes here from his home in Menlo Park, California where he lives with his wife, Donia Bijan, a Bay Area chef and writer. He also wrote while he was on a painting trips to Truro, Massachusetts on Cape Cod, where a number of his paintings get their start. He frequently goes on painting trips to a variety of sites in the United States, Iceland, Europe, and Asia. He has worked as a program advisor to the Artist Residency program at the Borgo Finocchieto in Italy.

Before answering my interview questions, Mitchell Johnson requested that we talk on the phone so he could get to know me better which might help create a more personable and conversational tone to the interview. In this conversation, I explained that since there are already many many interviews with him available online, I’d like to focus less on his history and more on his painting practice, what was most important to him as a painter, and how he managed to be so successful in his career.

Excerpts from the Pamela Walsh Gallery website bio.

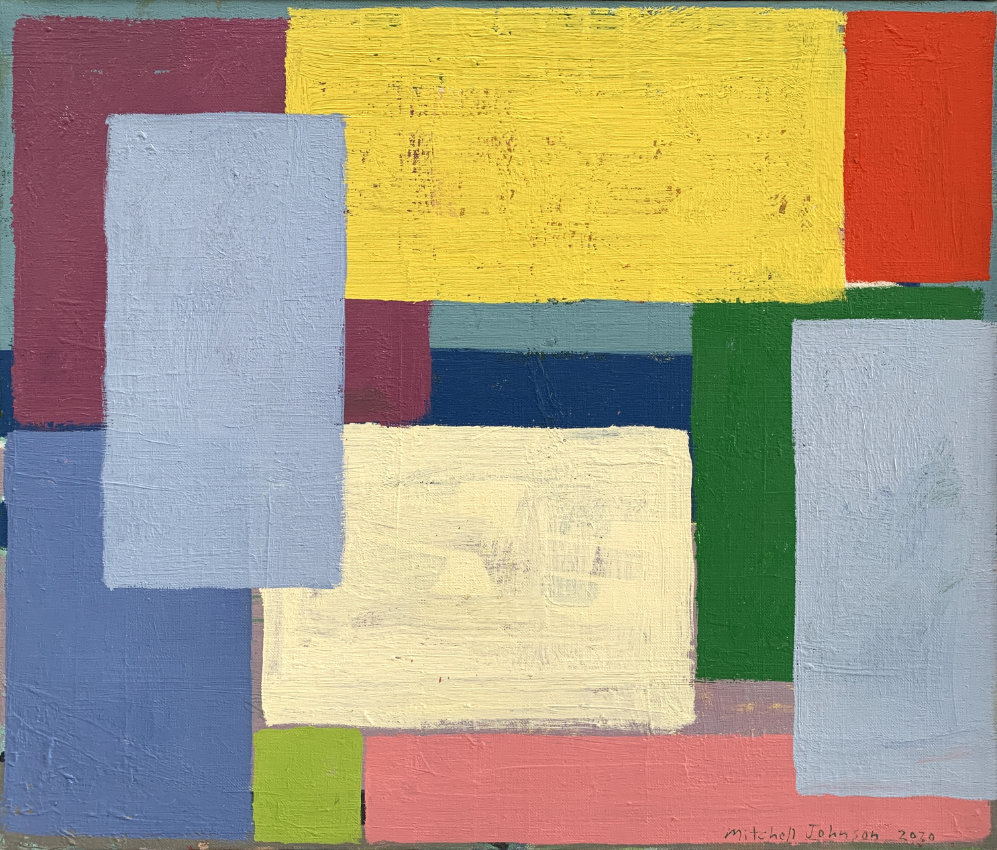

“Today, he works in a large, light-filled studio that allows him to deepen his exploration of colors in natural light and work on large-scale canvases. He is painting with the confidence of an artist who has spent years learning how to see; it is the art of sustained observation. Mitchell’s work dances between and within these two approaches with ease. It all becomes one language, one artistic statement; a dialogue about the continuum of color.

Mitchell Johnson divides his time between his studio in the Bay Area and his painting trips to New England, Europe and Asia. Throughout the 1990s, Johnson exhibited at major galleries in San Francisco (Hackett-Freedman, Campbell Thiebaud), New York (Tatistcheff Gallery), Santa Fe (Mitchell Brown Fine Art), Richmond (Reynolds Gallery), St. Helena (I. Wolk Gallery) and Los Angeles (Terrence Rogers Fine Art). Johnson has been a visiting artist at The American Academy in Rome, Borgo Finocchieto, the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation and Truro Center for the Arts at Castle Hill. His work can be found in over 700 private collections and the permanent collections of 29 museums including the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna, Rome; Crocker Art Museum; Oakland Museum of Art Foundation; New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe and Museo Morandi, Bologna, Italy.”

Mitchell Johnson studied with the painter Ray Berry at the Randolph-Macon College, Ashland, VA; B.S. (1986) He studied with Jo Weiss and David Holt at the Washington Studio School in D.C. and received his M.F.A. (1990) in painting at the Parsons School of Design, New York City. Where he studied w/ Paul Resika, Leland Bell, John Heliker, Robert DeNiro, Nell Blaine and Larry Rivers. He was also a Studio Assistant to Sam Francis, Palo Alto, CA, (1990-91) and studied with Wolf Kahn at the Santa Fe Institute of Fine Arts, Santa Fe, NM, in 1992.

Larry Groff: Your upcoming retrospective, Color Continuum: Selected Works 1988-2021, will be on view May 15 – June 26, 2021 at the Pamela Walsh Gallery in Palo Alto, CA. Does your show’s title, “Color Continuum”, refer to how the color in your work relates to past artists? Is color the subject matter of your paintings or is it something else as well?

Mitchell Johnson: Thanks for putting together such a thoughtful list of questions and for inviting me to try to explain why painting matters to me.

I hadn’t thought about the title suggesting anything other than color being the thread between my early small paintings in the exhibit and the most recent giant paintings. I owe a lot to the painters that have influenced me and continue to inspire me and if the title also suggests giving credit to the past that’s appropriate.

Color is the primary concern in my work, but by “color”, I mean the visual experience of the pieces of paint that make up a painting. Perhaps, instead of saying that color is the subject matter, it might be more clear to say that “how we see” is the subject. I’m trying to further open my eyes and by default the viewer’s eyes with a goal of seeing better.

I should make something really clear before trying to answer any other questions. When I paint I am not trying to show what I know or what I know how to do or report on what I have seen. There is no conscious metaphor in my paintings and I am not interested in realism. Each painting I make is an experiment, a trial to see if I myself can better understand color and if I can make something out of the overwhelming feelings I experience with certain color situations, certain patterns. Every painting is started in a different way and every painting is resolved in a different way (or abandoned). I’m not interested in what has worked before, which paintings people like, or which paintings have had critical praise because I’m just responding to the world and the painting I’m working on and trying to keep going without getting discouraged. I’m painting out of intuition for my own satisfaction, to answer my own questions. I often work on paintings for many months or years. I don’t return to older paintings to try to “fix” them. I return to them to continue them and as a way to allow time to be an aspect of their ultimate content and conclusion. Visual experiences really do overwhelm me and I’m painting to be a bit more grounded. The Continuum title is also a reference to how long I work on paintings, sometimes for months, sometimes for years.

LG: What are some important ways your work has evolved over the years?

Mitchell Johnson: As I answer these questions I am in Truro on Cape Cod, not in California and it’s early May and the weather here is changing day to day with some rain, some sun, some wind. I usually come here with my wife twice a year because she writes well here and I always get ideas for paintings and enjoy looking in person at the lot of the stuff I include in my paintings when I am in the studio in California. I first came here in 2005, when I was making a breakthrough, just after seeing the Morandi/Albers exhibit I frequently mention. Yesterday was so rainy and cold and gray that I didn’t do any work outside. I made a small drawing looking out the window and tried to answer some of your questions. I don’t like the answers I gave yesterday because they’re really long-winded – this is a second attempt, kind of like how I keep trying in a painting after a bad start. The core purpose of my work is to keep changing, keep seeing better, keep responding, keep making something new. One of the biggest evolutions that have occurred was in the early nineties when I could work on my paintings without being in front of the motif anymore. I made a lot of three-month trips to Italy and France around 1989-1995 where I rented a place in a small inexpensive town and did little but paint and read and write letters. I wasn’t in a school or hosted or there on a grant. There was no internet or social media to distract me and my only sense of purpose came from mixing a new color or making a new color relationship in a landscape I was working on. During those trips, I increasingly felt that I wanted to continue what I was painting outside when I got back into the apartment/studio. Seeing my painting on a white wall, away from the motif, I found what was most important wasn’t fidelity but an overall feeling from the arrangement of the colors and shapes, the formal life of the picture plane.

The next evolution was a desire to make large abstract paintings which started in 2003. I wanted to be inside, using very large areas of color, almost enlarged portions of the paintings I had been making in the 90s out in the landscape. I was looking intensely at other people’s abstract work and reading everything I could find on color theory in order to decide what I did and didn’t agree with concerning abstraction. I found that I really agree with Albers (his teaching and his work) but not with Johannes Itten. That I really agree with Hofmann’s teaching but not his paintings. Ultimately what I was seeking was not in abstraction. I wanted vitality, a mystery that could only come from the color relationships in the painting.

The third evolution was a realization that if the color was doing something special it didn’t matter if the shapes in the painting were identifiable or not. This is very significant in that I now include a towel or a water tower or a chair only if its color works. If its color doesn’t work, the color gets changed either directly or by what’s around it and if it still doesn’t work then I get rid of the “thing”, the shape.

LG: I’m curious to hear what your average day is like in your studio and your studio practice in general. How much do you plan out a painting with studies, drawing, and such?

Mitchell Johnson: I primarily paint in my studio which is a large warehouse with skylights and I work during daylight. I work on many paintings simultaneously and I often work on paintings for many years. As I drive the seven miles from my house to the studio I try to imagine how I will start when I get there. Some days it’s crystal clear that there was a thread from yesterday that I can pick up. Other days I get there and I feel completely discouraged and have no idea where to begin, even if I know three people want the next Truro painting or two people want a big NYC cityscape it may not help, I may not know how to start. It’s possible that I’ve sold a few paintings and I have to be ready for a shipper to pick something up or I have to frame and wrap paintings that will go to FedEx. I don’t trust anyone to package the small paintings so I box them myself and FedEx them overnight. I never ship by ground – it would stress me out wondering if they’ve arrived safely. I always wait for the email that the paintings have arrived safely and the collector really wants them. I know people think I’m bulletproof because of all of my ads and exposure but I’m actually a very anxious person about both painting and the business stuff.

LG: Do you use a particular palette of colors or do you like to change it up over time? How do you generally lay out your colors? What brand of paint do you use?

Mitchell Johnson: I mostly use Gamblin and Williamsburg oil paint and I have a big rolling palette and the paintings are on the wall as I work on them. There are screws in the wall so I can raise and lower the paintings as needed and the screws are positioned to hold paintings that are 20×28 inches up to 58×86 inches. My largest paintings are 78×120 inches canvases and those are simply placed on the floor or small boxes to raise them. I wouldn’t be able to make or store such large paintings without the warehouse. It’s a huge financial commitment, but I couldn’t work without it and making the big paintings is an important part of what I’m doing.

LG: Do you have an assistant?

Mitchell Johnson: I have a designer in Brooklyn who prepares my ads. I often spend time communicating with her and then I’m fielding emails in the morning before I go to the studio because of inquiries or shipping logistics. I get help with my website, and someone makes a lot of my big canvases, but I don’t have a studio assistant. This is a scattered response, but the days are often like that-unpredictable, not well organized. There is no typical day or routine especially when you consider that I travel several months out of the year and there is packing and unpacking and organizing trips on top of what I’ve mentioned. As I write this it starts to sound embarrassing, but it’s the truth.

LG: Do you just work on one painting at a time or have several paintings going on at once?

Mitchell Johnson: There is little structure in the studio and for the paintings, little planning, and no preparatory process. There is only excitement to work or sadly, no excitement to work. Frequently, I’m working on a painting trying to get a particular orange or green or gray to work and help the painting turn a corner and as I’m carefully mixing and considering the color I realize I’ve found the answer for a problem in a different painting that has been put away, perhaps a few weeks ago, but maybe one or two years ago. I go take it out and begin working on that one. I’m after a flow where the paintings are helping each other. I have no idea what it would be like to organize and plan a painting. I need to follow the painting unfolding and be open to where it wants to go.

There was a time when I loaded a small wooden palette and stood outside at a French easel as I am doing for a week here in Truro. For many years I used various garages in Palo Alto as studios and to store wet paintings. I also painted for two years under a giant tent I made from an old sail when I was living in an ancient piano crate in Palo Alto. The crate, my living space, was the size of three futons. I put the sail up right outside the crate and tied it to some trees and a garage so I had a fairly weatherproof area and that was my living and workspace for 1993-1995. I started renting my warehouse studio in 2009 after a six-year lease of a “studio” that was a classroom in an old Palo Alto high school expired.

I take out the colors as I need them and mix what I want when I’m ready. I’m trying to find new color combinations, new color experiences every time I paint whether I am working on something small that is fairly representational or something enormous that is essentially just blocks of color. I’ve arrived at this way of working after tons of trial and error and plenty of structured study. My teacher, Paul Resika, says we “go to the studio to do what we don’t know”. In the studio I am still trying to find answers – I’m not repeating what I’ve already learned. Even with the Truro paintings, lifeguard chair paintings, New York City paintings, or various paintings called “Race Point Bench”, I’m not comfortable referring to these as a series. I can imagine on Instagram people think these are all the same painting or that they are a series, but each one has been started in a different way and resolved in a different way. And some don’t get resolved and get destroyed or abandoned and become the jumping-off point for another painting.

My wife and I usually walk or swim together in the morning and then we have breakfast and then I get moving. I frequently drive to the studio six days a week, if not seven, especially now that my son is away at college. Sometimes I bring home small paintings to look at in our house, but many of my paintings are too big to bring into our house so I have to decide if they’re done by how they look in the warehouse. I mentioned traveling: I often go back to the same town in Italy called Buonconvento, near Siena, or to Truro on the Cape or one of several places in France. I have easels and paints stored in all of those places. I think there are still stretcher bars stored in Italy and France from more than 25/30 years ago when that all started. I bring some linen that can be stretched and then unstretched and rolled for bringing home. Needless to say, there are a lot of logistics. I love the trips but they are more stressful now that I’m a little older and too aware of things that can go wrong. But I definitely still travel. When I am traveling, I am looking for things that can be translated into paintings. I’m well aware that people don’t always understand what I claim to be doing so let me put it this way. I’m not trying to make a painting of a yellow picnic table, I’m turning the yellow picnic table into a painting.

LG: What can you say about why you chose architectural forms for your subject matter, like the many you’ve made in Truro, Cape Cod, Italy, and California? I see affinities with your treatment of this subject matter with painters like Fairfield Porter and Edward Hopper. Do you ever worry about seeming derivative? What are some ways your work departs from what they were doing?

Mitchell Johnson: It’s 5:30 am and I’m still in Truro and the sun is rising and after all of the years I’ve been coming here to paint there is yet another unique show happening out the window and the moment is so fleeting and remarkable that I truly cannot believe it. I found this spot, a bird’s eye view from a motel window and I’ve used these cottages in many paintings for about 15 years. The cottages behave like a still life that is constantly changing color and appearance with the time of day, time of year, weather. Hopper painted around here but I didn’t know about that when I first started coming in 2005. And of course, Porter was obsessed with Hopper but I didn’t look at either of them very much until I started to spend a lot of time in New England instead of in Europe.

I use architectural forms because of the endless possibilities for organizing the canvas and because they establish a kind of visual music. I think Porter is interesting because he always uses color before value even in the shade, especially in the shade. The reason I understand that about Porter is by way of Albers and Albers is the one that helped me see the potential in architecture to be anything a painting might need. Albers helped me understand that architecture could be the scaffolding not for reportage but for a color statement. I would never try to defend whether or not my work is derivative but I would say that if you saw my paintings in person you would realize that the color is my own, it is unique. You have to look at the painting, not the painting’s style or allegory.

LG: Why mix representational landscape with abstract geometric shapes? What are some of your thoughts about combining and unifying disparate elements like this?

Mitchell Johnson: We are completely free as painters to do whatever we want, to respond as needed. Isn’t that the idea? Painting isn’t a police report, it’s not about style or what was there, it’s about what you want to be there and what is in the painting. I take the painting where it leads me. I was never fond of David Salle’s paintings or Thiebaud’s early cakes or Lichtenstein when I was younger. But now I really enjoy their work for the simple fact that they acknowledge that anything, literally anything can happen in a painting.

[See image gallery at paintingperceptions.com]LG: You visited Reykjavik, Iceland back in 2014 and have since made a number of fabulous paintings of icebergs and the Icelandic countryside. Were any of these paintings done on-site or are they studio creations from memory and photos? Can you say something about your process in making these paintings?

Mitchell Johnson: My son, Luca, and I used to take a spring trip each year when he was out of school and we always researched where we would go by looking at photos of places to see if I would be interested in painting there. I’ve known the famous Icelandic paintings of Louisa Matthiasdottir since 1988 because she was married to my teacher, Leland Bell. Leland also made amazing paintings of Iceland and you should research them if you haven’t seen them. Luca and I found flights that would allow us to stop in DC and see my father and the museums and then have a week in Reykjavik before he had to start school again. I knew from our internet research and from Ulla’s and Leland’s paintings that I would find intriguing views in Reykjavik. I brought a sketchbook and some gouache and it was perfect that we looked at the Ralston Crawford and Stuart Davis paintings in DC at the Phillips just before heading to Iceland. We also got lucky that there was a giant Kjarval exhibit at the Reykjavik art museum. I had never seen his paintings in person. We missed the northern lights because my alarm didn’t go off. Still, the trip was very worthwhile. I had an amazing new digital camera and we climbed the church tower and had some good weather and I got some great ideas that led to a number of studio paintings.

Occasionally I’ve introduced an iceberg into one of my Iceland paintings but the iceberg I saw in person was in Bonavista, Newfoundland. Using icebergs in my paintings started after I saw the famous New York Times photo by Jody Martin of the 2017 Ferryland Iceberg. I add icebergs to my paintings the way someone else might add a cloud or a building as a way to introduce a challenging shape, a mass of white or off-white. The iceberg is a prop if you will get a color or shape where otherwise there isn’t one, but they also have an ambiguous scale like water towers, clouds, fabrics, or moments of architecture. Icebergs disrupt the picture plane in dynamic ways and I use them when the impulse arrives.

Full disclosure: the first two iceberg paintings I made were heavily based on Jody Martin’s photo and when someone wanted to buy them, I lied and said they were sold. I kept them for another year or so and once I had made some other iceberg paintings that felt more completely mine, I destroyed the first two. It’s great that I’ve seen an actual iceberg in person but ultimately as I’ve said, I’m using whatever it takes to make an interesting painting and I’m not relying on facts or things that I’ve seen. In general, I don’t paint about a place unless I’ve been there. But if I stumbled on someone’s photo and it was very much a photo I would have taken myself, it might lead to a painting.

LG: How have you been able to travel to so many amazing spots around the world? Does the selling of paintings you’ve made at or from these sites support this?

Mitchell Johnson: Yes, I generally sell the paintings that result from a trip. But as I’ve said, when I first went to Europe and New Mexico in the nineties, I was living very very cheaply. Adam Gopnik wrote an interesting review of Alexander Nemerov’s Helen Frankenthaler book, “Fierce Poise: Helen Frankenthaler and 1950s New York”. Maybe you’ve read the book and the review in the New Yorker. In the review Gopnik says:

“Another struggle is presented by Nemerov’s puritanical take on Frankenthaler’s concern for her career, too much remarked on in her day; she thought nothing of posing for a spread in a popular magazine if doing so would increase her fame and sell her pictures. Nemerov assures us that, nevertheless, “something saved Helen. Her paintings stood apart from her quest for recognition and sales.” Why, though, would she need to be saved from being sold? Being part of the world of buying and selling is constitutive of what the visual arts have meant and have been since the end of the medieval era. Only priests and academics find anything shameful in it. Whatever is lost in contamination by commerce is more than made up for by what’s gained in independence. Frankenthaler painted what she wanted, and people bought what they wanted.”

I’m a big advocate of independence and the freedom to paint anything I want.

LG: If you were to curate a show of the work of three or four living painters – who would you pick and why?

Mitchell Johnson: I’d pick paintings by David Holt, Tomory Dodge, Laura Vahlberg and Amy Weiskopf.. All of them give me ideas and they all are defending a certain approach to both painting and a view of art history that I agree with.

LG: What do you think about Matisse’s famous quote that “Art should be something like a good armchair in which to rest from physical fatigue.”? Is it enough for a painting to just have the pleasing formal concerns of colors, shapes, and patterns? What do you say to those who might say your work was more decorative than expressive? Decorative painting is sometimes considered a pejorative term – what are your thoughts?

Mitchell Johnson: I know the Matisse quote because at Parsons we were assigned both the huge Delacroix biography and the book, “Matisse on Art”. The Matisse quote I prefer is “tell a lie to tell a greater truth”. That’s how painting works-it has both limitations and strengths. By “lie” I think Matisse meant the painting’s shapes and colors are placed in a way to express something, not assembled and drawn out of a goal of accuracy or fidelity. My use of rectangles or buildings and chairs that weren’t there are inventions and inspirations. But they’re also creative risks that sometimes pay off and sometimes don’t.

When I was in Tuscany painting for a few months in 1996, a friend brought her parents over to see my paintings. Her parents had driven down from Denmark and seen a lot of landscape over the previous week. When they laid eyes on my twenty paintings scattered around the banged-up old farmhouse where I was living, their faces went blank. I’m 100 percent sure that they were disappointed and not sure what to say about my paintings or how to approach them. A few days later they spotted me in town at the Saturday market and they came over to me quite urgently and shook me and said, “Wow, we didn’t realize it before, but it really looks like your paintings around here!”

A few years later, I was still painting outside in Tuscany when after an hour or so of very focused work a saturated red tractor passed abruptly in front of me and it was towing an orange trailer with some contadini in their beautiful blue work clothes. I quickly took my strong orange, red, and blue and massed in some general shapes at the lower edge of my big landscape. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I was just starting this new conversation between manmade color and naturally occurring color and I was combining the colors of Albers with the colors or Morandi. But again, I didn’t quite realize what I was getting pulled into until a friend handed me some gorgeous color decks from his auto body shop. The color decks were references for old Fiats, old Vespas and for trucks and tractors – European enamel colors from the ’60s and 70s. I went back to the apartment and exactly matched these Fiat and Piaggio colors exactly with my tube colors and added little piles of the new colors on my palette next to piles of my tube colors. Then I went and compared the earth colors of the buildings with the soil colors and realized the houses or Tuscan “barns” that had been baffling me were actually the color of the earth, far from the color of the tube paint. I began mixing the earth hues into the Piaggio hues to get yet another range to my palette. Maybe I should have told this story above in reference to the evolution question. Often at the end of my landscape painting trips to Europe and even Cape Cod I have piles of wet paint on my palette and I now make tiny abstract paintings on pieces of cardboard or swatches of canvas and I place these little paintings in my storage so I will see them when I return the next year.

LG:The relationships between galleries and painters have changed a great deal since the 1980’s-90’s. Back then, exceptionally talented and visionary painters were more likely to find a gallery to show their work. Today, with the painter-population explosion and the implosion of the gallery scene it is almost impossible to persuade an established gallery to look at your work. These galleries seem less inclined to take risks or promote unknown artists and tend to be more oriented towards what’s known, art-world connections, and fashion than advancing the arts. My following questions come out of my curiosity about how you’ve maneuvered this difficult terrain over the years to become one of the rare painters who, presumably, does very well from your painting sales.

From your resume, I see that you showed for a time with the Tatistcheff gallery in New York. How did you first get started with showing your work in NYC? How different is getting into a gallery these days compared to what it was like in the ’90s?

Mitchell Johnson: I’m back in California now and we just installed my exhibit at Pamela Walsh Gallery a few days ago and it was very stressful seeing how different my paintings look away from the studio, in a big group, in a commercial space. There’s something so flattering and exciting about an exhibit but it can also be a rough time because the paintings are really changed by the new context. This is not a comment about Pamela’s gallery – she has an amazing space with high ceilings and she’s giving the public a chance to see my paintings, something I can’t do. She’s put enormous effort into planning and presenting this show in her new space and my show is following a rare exhibit of Nathan Oliveira’s work. You asked about Tastistcheff gallery in New York and we are both old enough to know that it was a big deal to show in a place like that on 57th Street in the 80s and 90s. The internet and social media have democratized the gallery scene so that most galleries are seen as the same as all of the others and people simply care about sales and not so much about who else the gallery shows with, or even the reputation of the dealer. The public just wants to find work they like and respond to.

In the past, I think collectors had a long-term relationship with various galleries and built collections over a lifetime and it was very much a long-term ongoing relationship with familiar faces at openings and writers and critics and artists supporting each other by attending exhibits. And collectors felt they were supporting the arts and not just decorating their homes. But that doesn’t answer your question about how I ended up working with Peter Tatistcheff. In my experience, the art world is just like life: it’s a combination of things that you pursue and try to make happen and then there are also things that fall in your lap. You’re trying really hard to get a gallery to pay attention to your work or give you an exhibit. Then someone had a last-minute exhibit cancellation and you are ready to go and you’re suddenly in a gallery that wouldn’t even talk to you before. You have to leave the house, get out into the world and not wait for people to knock on your door or discover you.

I made a lot of effort to send slides to galleries in the nineties as soon as I finished graduate school at Parsons. I was painting landscapes that really mattered to me. People wanted them and there were plenty of galleries willing to consign a few paintings and try to sell them. Occasionally they put me in group shows, even shows with people like Wolf Kahn and Nell Blaine and it was kind of random, but it looked good on my CV. I did pursue the dealer, Jeff Mitchell, in Santa Fe and that worked out and we showed together for years and he was my primary source of income and exposure for six or seven years. Jeff helped get some of my paintings into museum collections and showed my work alongside of very important historical painters. He really went to bat for me and I will never forget that. By the time I met Peter Tatistcheff in LA my efforts and some luck and the work of Jeff Mitchell meant I had a resume of significant group shows and Michael Hackett in San Francisco was showing my work and he was becoming a powerful dealer and that would have impressed Peter.I showed in Peter’s west coast gallery in LA and he needed to try something new in New York and the next thing I know I was having a very major exhibit that I hadn’t really pursued. After moving away from NYC following grad school in 1990, the exhibit at Tatistcheff felt like a triumphant return in 1996. Several people told Peter they were going to review the show and then neither did because he forgot to follow up with them and I should have been more proactive in sending the info to the critics. I’ve never forgotten how we lost that opportunity. Unfortunately, Peter was getting older and went into debt and then the internet completely changed the specialness of a gallery on 57th Street and he moved to Chelsea and wasn’t able to adapt.

I have no idea what it’s like for young artists now using social media and the internet to build a reputation or following. I used social media and the internet to spread a story I already had. I feel for anyone using it to try to create a following. Again, I’ve provided a rambling answer, but maybe that reveals that my work with galleries has been off and on, rambling, random.

LG: For the past number of years, would you say that your advertising with the New York Times, the New Yorker, and others have been your de facto gallery in a sense? Your blog lists various advertising ventures you’ve made in major publications such as Art Forum, back covers of the New Yorker, inserts and full-page ads in the New York Times, New York Times Magazine, and others.

In an article from the Nobhill gazette

“…Johnson has been unusually successful for a visual artist, especially considering that he has never been part of the gallery system. He has also never had to teach in order to support himself and his family. Thanks to inserts in the New York Times (done years ago) and ads in the New York Times Magazine (ongoing), Johnson has found a receptive audience for his work. His website is his primary sales vehicle and, as he explains, “People see the work, send me a check and I send them the painting.” His philosophical take on the whole process: “It’s like a message in a bottle that you release into the world and you never know who is going to open it.”

I wonder if even blue-chip galleries would take out a back cover ad in the New Yorker so I’m intrigued by this and how it’s been working for you. Can you tell us something about what led to your decision to represent yourself on your own? Do you worry that some might say you’re going over the top with self-promotion and that advertising like this could affect your reputation negatively?

Mitchell Johnson: Yes, those magazines and publications you mention are my de facto gallery since many of the galleries I worked with for years either went out of business or didn’t want to show my work as it evolved. My ads are not directed at my family, friends, or other artists. The ads are directed at people who respond to my work. After years of showing in galleries that did a good job of finding collectors for my paintings, when the 2008 recession hit, it occurred to me that I couldn’t and shouldn’t ever rely on anyone to play that role again.

I watched for years as artist exhibits were advertised in ArtNews and Art in America and occasionally I convinced a gallery to split the cost of an ad with me. It usually paid off. In 2010, I received a Continuing Education flyer from Stanford University in my Bay Area Sunday New York Times. I wondered how that happened and after two years of investigating and planning to do something similar myself, I rolled the dice and started inserting my own catalogs into the Bay Area New York Times in 2012. I met a lot of new people through the catalogs and sold paintings. I didn’t initially run an ad in the nationwide NYT Magazine as I do now, I inserted a printed catalog. Eventually, the printed inserts became mostly ads and later the New York Times project expanded to other publications. I now work with The New Yorker, WSJ. Magazine and Artforum. My show with Pamela Walsh Gallery is advertised in all of these publications.

LG: Many painters who teach or others aren’t dependent on sales to support their family and craft, denounce the popular commercialism of art and instead advocate that making art should be something that about making something that is unique, new, has political-social importance or that advances various formal visual concerns or expressive considerations. What is your take on this subject? How much do sales affect what you decide to paint? If no one buys the hypothetical paintings of, say–angry and dark “dumpster fires” but the bright and cheerful paintings of beach scenes fly off the rack, how much would that determine what and how you painted?

Mitchell Johnson: I paint what I want to paint. The Gopnik quote I mentioned above sums up how I view the freedom I have due to the ads. I lease advertising just as a gallery leases a space.

LG: Your promotional material sometimes makes it unclear that you are paying for advertising when a publication like the Art Forum has a spotlight section on your work. Won’t this confuse someone who isn’t as familiar with the difference between a review from a staff writer and paid advertising? Or is that the point – in the hopes that this will elevate your standing and importance in the art world and consequently the desirability of your artwork?

Mitchell Johnson: The world and especially the art world are very confusing if you don’t look closely and pay attention. If you read and take your time, it’s clear what is editorial and what is advertising. I sell my paintings to the people who want them, the people who have encountered them. I’m offering opportunities for people to discover my work. About 800,000 people still subscribe to the printed Sunday New York Times. Every week someone writes to me after seeing my work for the first time in a magazine.

LG: I’ve read about how you’ve stated that Morandi and Albers, as well as other artists such as Fairfield Porter, Bonnard and others, have been hugely important to your growth as an artist, yet the connections aren’t obvious. Your often saturated color choices seem to be going after the vibrant colors of life and light in California or Cape Cod – rather than that of Morandi’s fresco-like powdery pale tones. Albers used very few carefully arrived at colors and he eliminated representational considerations with his color interaction studies, your work, especially with the paintings combining abstract elements is often highly activated with many colors. With that in mind, why do you frequently bring attention to your affinities with Morandi and Albers? I understand that artists often explain what they are trying to accomplish by what this has in common with great painters of the past, a shorthand to letting others know where you fit in. What would you say to a cynic who says this is just a marketing tool to connect your name to them?

Mitchell Johnson: I find that Morandi and Albers are both talking about perception and context in their work. They are both talking about how we see, not so much how things look, but how we see. Most of the painters I like and look at are talking about how we see: Chardin, Jane Freilicher, Corot. I think that’s why painting is still relevant because it can comment on how we see not just be a report on what was there. Albers is drawing attention to the numerous faces each color possesses, to how any color is vulnerable to the influence of other colors and context in general. Albers is talking about how a colors personality is different depending on how much of it there is and what is near it. Morandi likewise is talking about how forms are influenced by the presence or absence of other forms. How scale is a very complex assessment that is constantly in flux, like Albers is talking about color is constantly in flux. Morandi’s clusters of bottles and objects are like people huddled in a room and they change depending on who is there and who is not there. Scale is such a big part of how we make sense of the world and experience color and there is a lot of commentary on the scale in the work of all of these artists that I always refer to. What I’m suggesting is that my concerns are similar: the effect of context, the flux of color and scale, the ambiguities of visual experience. Morandi’s color is different from Albers but it is equally important to him, equally articulate and you feel the importance of his color choices, even more, when his work is exhibited alongside Albers. If you place Albers next to Hofmann, it becomes clear that Hofmann’s color feels random, unconvincing. If you combine Morandi’s color with the color gamut of Albers you get a palette that I often use.

LG: Now that you are connected with the Pamela Walsh Gallery will you still be advertising and selling your work on your own after this show?

Mitchell Johnson: I’m not sure what the future holds. But I’m very grateful for this opportunity Pamela has provided. I hope we can continue to work together and she can handle a lot of things I currently manage so I can stop running ads and just paint. The prices of my paintings are the same either way. I generally raise them every year, sometimes sooner if too many are selling. The prices didn’t go up because I’m showing in a gallery again.

In conclusion, I want to add something about the NY Times partnership because it has been really important to me. When I went to meetings at the actual NYT building on 8th avenue around 2013/2014 I was just getting interested in cityscapes again. I couldn’t believe how their view of water towers and Hudson Yards construction was calling to me. There was something very compelling about the scale and space that I wanted to explore. They let me come back with some blank canvases and over the years I’ve made drawings from inside of the NYT building looking down at the Port Authority where I had been several times with my parents when I was a boy. I could almost see 39th street where I had worked in a basement helping Frank Stella’s assistant, Earl Childress, assemble his paintings when I was a student at Parsons in 1988. I could see various Chelsea buildings where I did construction jobs when I was a Parsons student. I’ve claimed that there is no allegory in my paintings, but I definitely think about my deceased parents when I make NYC paintings and it makes me feel closer to them. And the Truro buildings are reminiscent of my grandparents’ very modest houses in South Carolina and Florida. I just might be painting more about memory and nostalgia than I ever directly acknowledge.

The post Interview with Mitchell Johnson appeared first on Painting Perceptions.